A small, dilapidated school in Beijing is providing migrant workers with the basic knowledge they require to make a comfortable living far from their homes in the countryside, as Xin Dingding reports.

The "Workers' College" is probably the smallest, shabbiest educational institute of its kind in Beijing.

The training center for migrant workers occupies a rented campus at an abandoned primary school in the northeastern suburb of Pinggu. On a warm April morning, students sat in a dimly lit classroom and took notes as they hunched over second-hand desks of different sizes and colors.

Although the conditions are far below average, the students, mostly aged between 16 and 25, enjoy free tuition, dorms and meals. The full course lasts six months. In return, they work one day a week at an orchard the school has rented. The school has capacity for 50 students, but this semester, which runs March through August, there are just 19.

There are no formal entry requirements, but prospective students are interviewed about their working experiences and backgrounds. Few have had more than nine years full-time education, and some only attended primary school, but they all have experience of working in factories, on construction sites, or other types of manual labor, as evidenced by the coarse, tanned skin on their hands.

Since 2009, the college has been giving lessons that other training institutes seldom provide - lectures that help the students gain a better understanding of their own skills and aptitudes, and broaden their horizons. They also learn about the history of migrant workers, and study the labor laws so they know their legal rights.

They can also learn practical skills, such as fixing PCs and using computer software, that will give them a wider range of choices in the job market, and are also given the opportunity to learn how to run an eco-friendly orchard or take up internships at NGOs that focus on public welfare.

Sun Heng, one of the founders, said the college was established to teach a range of essential "city-living" skills that will enable migrant workers who left their rural homes at an early age to earn a living in the urban environment.

His philanthropic instincts were also roused by a string of 14 suicides among young workers at a factory in Shen-zhen, Guangdong province, owned by Foxconn Technology Group, where smartphones and iPads were made for Apple Inc. Sun said the news made him aware of the predicament facing many young migrant workers, and the confusion and despair many of them feel. Those feelings prompted him to do something to help them.

Back in 2002, Sun was one of a group that founded a nonprofit organization called Migrant Workers' Home, which was devoted to providing a cultural life for workers in the capital. The organization also founded a primary school for their children in 2005, in the belief that education would exert a positive influence on young minds. "We wanted to open more windows for them," he said.

Running out of options

Sun has spoken with many migrant workers of different ages, but those born in the 1980s and 1990s strike him as being very different from their parents.

"Their parents left home in the 1980s to earn money in cities. They endured the harsh working conditions because they knew they would return home one day and spend their remaining years in the village. But the new generation of migrant workers has adapted to urban life, and they want to stay in the cities," he said.

Some members of the younger generation have no land to return to. Qin Chunxia, a 24-year-old student at the college said returning home is not an option for her, because she, her younger brother and sister no longer have fields to tend in her village in Liuzhou in the Guangxi Zhuang autonomous region.

"Our family of five used to rely on just a small patch of land assigned to my father in the 1980s, but it has been requisitioned. My parents now earn a small amount working on nearby construction sites or by helping other farmers grow watermelons," she said.

Moreover, many workers from rural areas don't even know how to work the farmland. Liang Dong, 32, said he had barely done any farm work before he left his village in Liupanshui in Guizhou province, at age 17. However, he wasn't sorry about that. "Farming is too tiring and the income is too low," he said.

Still, becoming a part of the city is equally hard.

Liang has lost count of the number of jobs he's had in the past 15 years, but none of them paid enough for him to settle down. He has lived and worked in a number of cities, and earned a living on construction sites, and as a waiter, factory worker, security guard and bookseller. He declined several offers to attend junior college, partly because he didn't want to use his parents' money at a time when he was unable to earn enough by his own efforts.

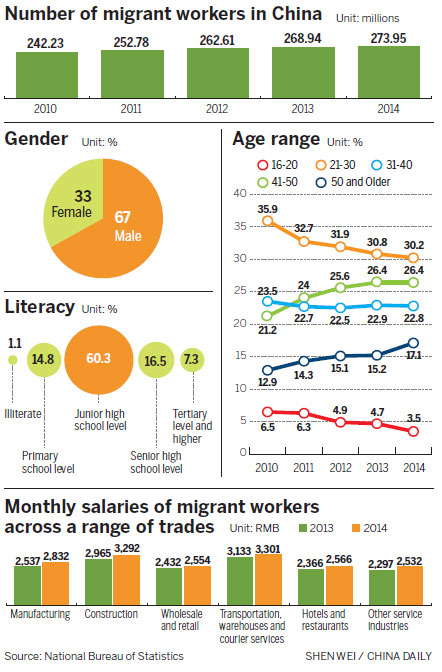

In April, the National Bureau of Statistics published a survey on the lives of migrant workers, which showed that their average monthly salary was just 2,864 yuan ($461) last year. Despite being a year-on-year rise of 9.8 percent, that increase is paltry when compared with soaring urban property price, especially in China's larger metropolises.

To earn an above-average salary, migrant workers usually have to work long hours. The NBS report said that most work 25 days a month on average, while 85 percent work more than 44 hours per week, and conditions are tough.

At her last job, at an electronic equipment factory in Shenzhen, Guangdong province, Qin was required to work 12-hour shifts, and "everyone had to work frequent night shifts, from 8 pm to 8 am, standing at their workstations all night long".

Sadly, these low-paid jobs often result in a lack of respect for the workers, and sometimes even humiliation.

Liang said the longest he ever stayed with one employer was a year, but he left the job - as a company security guard - because he felt he wasn't getting the respect he deserved. Things came to the boiling point when Liang refused to allow a white-collar worker to take a shortcut and enter the complex through the exit gate he was guarding. "He cursed me loudly because I stopped him, and eventually, we ended up in a brawl. My superior came, but did nothing about the man. I felt vexed at the level of disrespect shown to me," he said.

Lyu Tu, who has a PhD in developmental sociology, is a researcher at the workers' college. She has interviewed more than 100 workers and worked at two factories to gather material for her book China's New Workers: Culture and Destiny, published in January. Lyu discovered that many factory managers don't treat the workers as human beings, but as production tools. At one of her jobs, at a factory in Suzhou, Jiangsu province, she said the managers "never called the workers by their names", not to mention that the owners ignored the workers' calls for decent housing, medical care, elderly care and education for their children.

Material wealth

A large portrait of Chairman Mao Zedong and an outdated calendar hang on the wall of the teachers' office at the college. The calendar, which showed October 2014, carried a photo taken several decades ago when the working class was regarded as the most important group in Chinese society.

But the old times have gone. Sun said many people now are ashamed of being workers, saying that the word "worker" has almost become a synonym for "uneducated" and "disadvantaged party" in a society that judges a person though a prism of material wealth.

He said many younger migrant workers have attempted to run small businesses and become their own bosses, and even employ a few of their peers, but very few have succeeded in achieving a stable, high income. Others harbor unrealistic dreams of suddenly becoming rich without hard work. Many of the 100-plus migrant workers Sun has interviewed told him that they bought lottery tickets, joined pyramid-selling schemes and even broke the law to make quick money.

"It struck me that people's sense of worth has gone astray. Workers should be proud of what they do," he said.

Some of the college's 200 graduates have used what they've learned to help other workers, according to Sun, who said one of them has established an NGO in Shaanxi province that works to safeguard migrant workers' rights, while another founded an organization in Fanyu, Guangdong province, to help women with work-related injuries.

He acknowledged that his work is a drop in the ocean, but remained upbeat: "The number of young people we can influence is tiny, compared with the millions of young migrant workers out there, but I believe someone must take the first step."

Contact the writer at xindingding@chinadaily.com.cn

|

Zhuang Yizhan, a student at the Workers' College, awakens to prepare for school. The institute for young migrant workers provides free tuition, sleeping quarters and meals. Photos by Feng Yongbin / China Daily |

|

Students relax in the reading room during the lunch break. |

|

Qin Chunxia (right), a student from Guangxi Zhuang autonomous region, has lunch with classmates. |

(China Daily 05/21/2015 page6)