The conflic that changed China

|

|

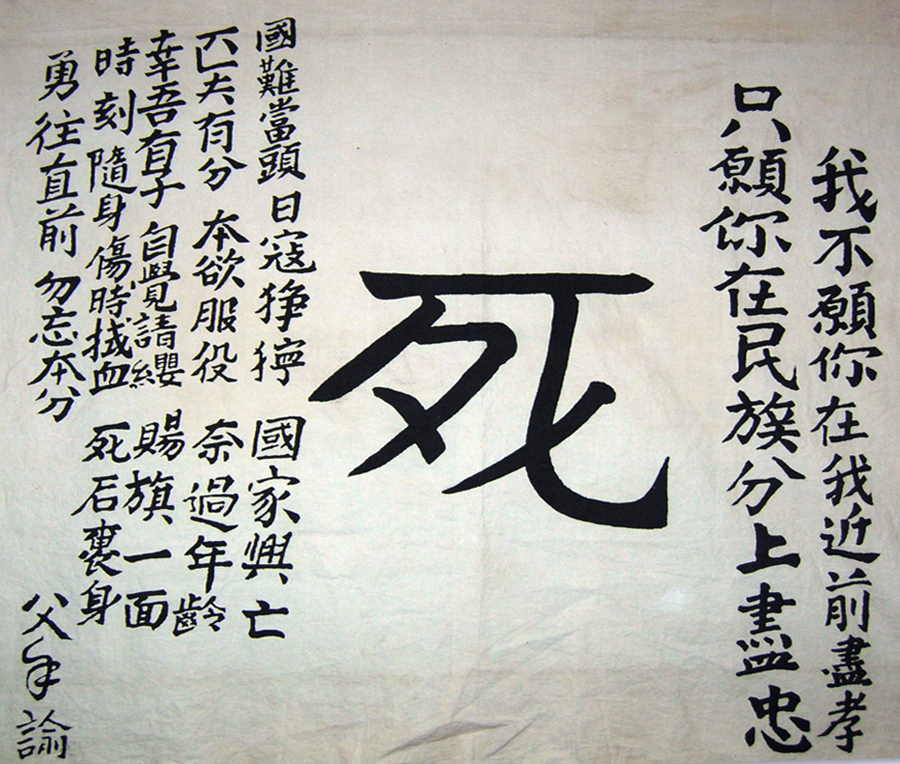

A reproduction of a letter given to Wang Jiantang by his father on the eve of Wang's departure for the front. CHINA DAILY |

The demand was refused, and at about 5:30 am on July 8, Japanese artillery began pounding the area. According to Hu Zongxiang, a soldier stationed nearby, the bombardment "destroyed five buildings, killed two people and wounded five".

The next few weeks saw sporadic fighting erupt between the two sides. Discussions were held, but Hong Dazhong, then-secretary of the Wanping government, believed the talks were nothing more than a Japanese ruse.

"For one thing, they were bringing in more and more troops. I knew they were newcomers because their dust-covered fatigues suggested they were at the end of a long journey, and their hats were unlike those worn by the soldiers I'd seen here for a long time," he said. "There were many artillerymen among them, busily unloading canons onto the platforms of the train station."

It was later revealed that the soldier, Private Shimura Kikujiro, had returned to his barracks at about 1 am on July 8, but his brief disappearance was used as a pretext for conflict.

Search for witnesses

Both Hu and Hong appear in video interviews released by the museum in preparation for an exhibition that opens on Friday, the 80th anniversary of the incident. Between 1999 and 2002, museum researchers-including Luo Cunkang, 47, now the museum's deputy director-conducted interviews with survivors and witnesses nationwide.

"During those years, we traveled all over China looking for people who were part of that crucial event. Sadly, all those we spoke with have since passed away," he said.

Cao Yi, 49, Luo's colleague and fellow researcher, remembers the veterans vividly. "The moment they started speaking, they were no longer men in their twilight years, but hot-blooded youths who thought nothing of dying," she said.