Residents feared to walk the streets, facing the threat of torture or death

Survivors of the Japanese occupation of Hong Kong have never forgotten the grim struggle for survival from 1941 to 1945.

Even those who carried on their day-to-day business to support their families did so at the risk of their own lives.

Ho Hing-on, 83, recalls how his mother, who was eight months' pregnant at the time, had to search for every cent at home in an attempt to secure the release of Ho's father from Japanese military police.

With the money she gathered, she paid to visit her husband who was being detained at a Japanese military checkpoint in Admiralty district.

He had been carrying two buckets of cookies and candies to sell when he was detained, but the Japanese were adamant that he had stolen the goods and tortured him, demanding he reveal the source.

He was choked by water being poured down his throat and beaten with rods. His ordeal lasted for almost a day.

"The cookies and candies were from our grocery shop in Wan Chai," Ho said. "My father hoped to earn money for the family by selling them at the Central Market, where there were still many wealthy people."

The extra money was needed because business at the shop had been poor since the Japanese invaded Hong Kong in December 1941. The price of daily necessities had risen dramatically and each day it became more difficult to provide for the family.

'Stuff of dreams'

Kelvin Chow Ka-kin, a senior project officer with the Hong Kong and South China Historical Research Program at Lingnan University, said that by early 1942 the price of daily necessities and food had risen as much as four times since the days just before the Japanese invasion.

Chow has been studying the lives of Hong Kong people during the occupation for 20 years.

When Ho's father recovered from the Japanese torture, he continued his daily pilgrimage to the Central Market, risking further cruelty and even death. "He had no choice ... because he had to raise his family," his son said.

The Japanese had seized most of the food supply. The population of Hong Kong was left with only 20 percent of the original stock, and the public paid dearly for the supplies they needed.

Lam Chun, now 80, lived with her family of five in Ta Kwu Ling Road, Kowloon, during the occupation. Her mother ran a school, but the students stopped attending classes. Her mother had to sell the chairs and desks so the family could buy food.

"The white rice we had for meals previously became the stuff of dreams after the Japanese occupation, during which we only ate porridge with sweet potatoes. Rice was rationed, sometimes as little as 160 grams per person per day," Lam said.

This was about a third of an adult's daily requirement. Lam stayed at home preparing meals, while other family members went about the city to scavenge for anything they could get.

"My mother stopped me going out because it was too dangerous outside," Lam said. "Cooking, eating and sleeping comprised my daily existence."

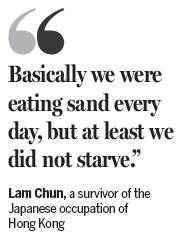

Cleaning rice took much of her time, as it was of poor quality and mixed with sand and pebbles. "Basically we were eating sand every day, but at least we did not starve," Lam said.

From the balcony of her home, she saw many on the road dying from starvation or exposure to the cold. "Some who were alive in the evening were found dead in the morning. The cleaners would cover the dead with a mat and take away the bodies," she recalled.

Always worried

Ho saw people lining up beside the sewer outlet of a Japanese restaurant near her home, each holding a sieve and waiting to catch waste that poured out into the sewer.

Each time the food waste was flushed, they rushed to the spout to collect what they could. "They made meals with the rice sifted from the waste," Ho said.

Yau Yat, a senior lecturer at Lingnan Institute of Further Education, has interviewed dozens of survivors of Hong Kong's occupation. People living in urban areas suffered more than villagers in the New Territories, he said.

"Villagers could grow some food, but people in the city were always worried about where their next meal might come from," Yau said.

Some villagers swapped food for other necessities with people from the city. Even villagers in remote areas would be harassed by the Japanese. Chow, from Lingnan University, said he had heard similar accounts during his research.

Leung Sau-lin, now 83, who lived in Mong Kok during the occupation, told Chow she had seen villagers buying secondhand clothes on the streets with money earned from selling homegrown crops to people living in urban areas.

Secondhand clothes appeared in the markets in Wan Chai, Yau Ma Tei and Cheung Sha Wan during the occupation. Some vendors sold their own clothes and clothes of their family members who had died. Ho said instances of selling clothes removed from dead bodies lying on the streets were not uncommon.

Chow said that during wartime survival became the priority, and people had to lower their standards and try their best to overcome the difficulties and challenges facing them. They became increasingly enterprising as a result.

In the late 1930s, especially after the occupation of Guangdong province, nearly half a million refugees fled to Hong Kong, swelling the population to 1.6 million by 1941.

The Japanese army concluded that the city lacked the resources to sustain such a large population and began driving those from China back to their hometowns. A commission formed to oversee this offered free rice and transportation across the border.

People whose hometowns could only be reached by foot walked for days, carrying their possessions in two buckets suspended from their shoulders, Ho recalled.

"Some were really miserable because there was a high chance that bandits would rob them of their belongings ... many starved to death before they could step outside Hong Kong."

When the Japanese surrendered in 1945, Hong Kong's population had fallen to 600,000.

Forgotten too soon

Chow said the Japanese occupation of Hong Kong, which lasted three years and eight months, put every family in the city under great stress. He said the city's younger generation, after learning the history of the struggle for survival, should draw a lesson from those dark days.

But Yau said young people in Hong Kong show little regard for this time in history. "They seem they are reading about the history of other places, not the place where they live."

Yau said textbooks portray Hong Kong as one of thousands of battlefields spread over a vast area. Students learn of the failed last stand of the British against the invaders, but seldom learn of the sacrifices made by the people of Hong Kong.

"Young people should learn the complete history of Hong Kong, not only about its economic takeoff in the 1960s as a British colony, but also about its darkest and most miserable period," Yau added.

frannie@chinadailyhk.com

|

Lam Chun's sister Lam Tsim (second from right) was the first one in her family to join the Dongjiang Column to fight against the Japanese army. |

|

Lam Chun joined the Hong Kong Independent Battalion of the Dongjiang Column. Photos Provided to China Daily |

(China Daily 08/28/2015 page5)